Dr. Seuss Returns to the Ninth Circuit for Misuse of Fair Use

Dr. Seuss Returns to the Ninth Circuit for Misuse of Fair Use

By: Dana Stopler

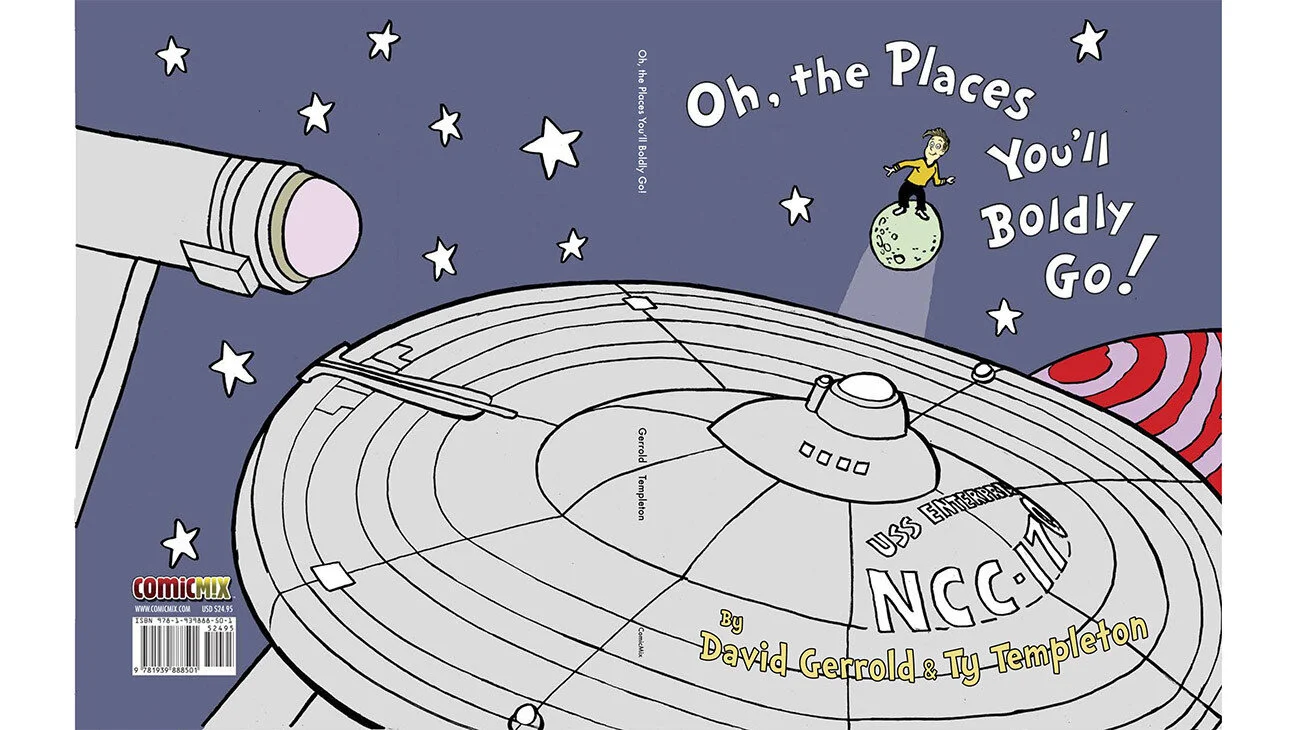

Credit: United States Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit, Attachment to the Opinion in Dr. Seuss Enters. v. ComicMix.

Mashups & The Value of Creative Play

Creative pursuits naturally borrow from cultural works that proceed them. [i] Mashups, the name given to creative endeavors that intermingle pieces from two or more preexisting works, perhaps refer to their sources of inspiration more visibly than other art forms. [ii] Mashups allow creators to pluck familiar symbols from film, music and media, and re-contextualize these elements by combining them into a single, unique work.

While the term, “mashup,” rose in popularity within the music industry and often refers to music and video remixes, now the term also encompasses genre-bending literary works. [iii] The 2006 studio album, Night Ripper [iv], released by the musician Girl Talk; the 2009 novel, Pride Prejudice and Zombies [v] authored by Seth Grahame-Smith; and the 2015 YouTube video, “Old Movie Stars Dance to Uptown Funk,” [vi] are just a few illustrations of mashups that recycle pieces of pop culture into novel sounds and stories. Regardless of the form taken, mashups have not only unlocked an innovative way to enliven preexisting work with new meaning or relevance, but also have unlocked a new means of expression. [vii]

However, when putting a mashup together, it is common practice for artists, many of whom are amateur creators, to use copyrighted work without permission from those who own the original materials. [viii] Therefore, mashup creation is often subject to copyright infringement—especially because the Supreme Court has largely declined to recognize mashups as transformative works and grant them with fair use protection. [ix]

Nonetheless, a literary mashup of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek called Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go!, has recently managed to skirt around copyright restrictions by qualifying as “fair use.” While this designation initially seems like a victory for mashup artists who have long struggled to receive fair use protection for their creative work, the transformative value of this particular mashup is hotly contested. Indeed, the book mashes together the disparate worlds of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek, but its story and message have remained relatively the same as Dr. Seuss’s original work, Oh, The Places You’ll Go!.

When analyzed in the context of three seminal copyright cases that elucidate the meaning of transformative for the purposes of fair use protection, the mashup hardly seems to satisfy the established criterion. Consequently, this current decision could open the floodgates for those who wish to exploit a lowered transformative standard in copyright law, thereby compromising the creative integrity of mashups.

A Look Into the Case, Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix

In late 2016, ComicMix, a publisher and distributor of webcomics, raised nearly $30,000 during a Kickstarter campaign to launch a newly minted literary mashup of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek titled, Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go! (“Boldly”).[i] The book mixes elements from Dr. Seuss’s classic works with characters and imagery from Gene Roddenberry’s science fiction franchise, Star Trek.[ii]

However, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the company that manages the intellectual property rights of Dr. Seuss, sued, claiming that that the mashup infringed upon the copyright of the book, Oh, the Places You’ll Go! (“Go!”), and swiftly shut the campaign down.[iii] Now embroiled in an ongoing copyright debate, the creators of Boldly maintain that the unauthorized incorporation of Dr. Seuss’s copyrighted materials into their book constitutes “fair use” and, thus, protects the company from infringement liability.[iv]

In 2017, ComicMix moved to dismiss the lawsuit. The United States District Court for the Southern District of California, initially disagreed with the company’s argument that Boldly qualifies as a parody and, therefore, should receive the broader fair use protection often afforded to works of that nature.[v] Nevertheless, although the court could not discern any parodic intent in ComicMix’s book, the court found that Boldly, as a mashup of two popular works, was “no doubt transformative.”[vi] Yet, the issue of fair use presented questions of fact that the court could not settle at this stage of the proceedings.[vii]

When the case returned to the same court, on March 12, 2019, to resolve cross motions for summary judgement, the court affirmed that the mashup was indeed “highly transformative,” and, as such, protected by the fair use doctrine.[viii] Overall, the district court concluded that while ComicMix copied literary and pictorial elements from Go!, these elements were adapted and ultimately “transformed.”[ix]

As of December 4, 2020, Dr. Seuss Enterprises has appealed the ruling and the Ninth Circuit is deliberating[x] over this unprecedented application of the fair use doctrine that seemingly grants mashups with a presumption of transformative value. [xi]

Tracing Transformativeness Through Case Law

The doctrine of fair use serves as a defense against copyright infringement by condoning the unauthorized use of copyrighted work in certain circumstances.[i] Accordingly, the legal doctrine ensures that courts won’t rigidly apply copyright rules when doing so would stifle the creativity that the law is designed to foster.[ii]

By codifying the doctrine in the Copyright Act of 1976, Congress established four non-exclusive factors to evaluate whether a particular use of a copyrighted work is “fair.”[iii] Here, the following discussion will focus on the first factor, the purpose and the character of the use, and to what extent a new work is transformative.[iv]

To conceptualize such an abstract standard as transformative, courts have traditionally drawn on Second Circuit Judge Pierre Leval’s 1990 Harvard Law Review article, in which he articulated that “a quotation of copyrighted material that merely repackages or republishes the original is unlikely to pass the test.”[v] On the other hand, if the quoted matter “adds value to the original” or is used as “raw material” to create “new information, new aesthetics, new insights, and understandings—this is the very type of activity that the fair use doctrine intends to protect for the enrichment of society.”[vi] Thus, fair use safeguards transformative works that creatively tinker with preexisting material to spark new, meaningful expression by guaranteeing “breathing space” within copyright law.[vii]

The question of transformativeness is central to fair use protection, but the interpretation of transformativeness oftentimes invites musings from courts that either clarify or confound the meaning of the term.[viii] While transformativeness may be the cornerstone of fair use, it remains a slippery standard to apply.

Appraising a Work’s Transformative Value

The meaning of transformative use was first introduced by the Supreme Court in the 1994 Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music decision. Guided by Judge Leval’s article, the Court established that a transformative work is one that does not merely “supersede the objects of the original creation,” but rather “adds something new, with a further purpose, or different character,” thereby altering the original work with “new expression, meaning, or message.”[i] On the contrary, if the work in question has “no critical bearing on the substance or style” of the original creation, such that the alleged infringer copies for “attention or to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh,” the new work’s “transformative” value and its claim to fair use protection diminishes.[ii]

Subsequently, in considering to what extent 2 Live Crew’s parody of Roy Orbison’s song, “Oh Pretty Woman,” was “transformative,” the Campbell Court determined that the rap group’s musical work was considered fair use because it commented on, and to a certain degree, criticized, the naivete of Orbison’s original piece. [iii]

Credit: United States Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit, Attachment to the Opinion in Dr. Seuss Enters. v. Penguin Books.

Restricting the Reach of Transformative Value

Notably, the Campbell Court stopped short of granting all creative pursuits that reappropriate preexisting work safe harbor under fair use by drawing a distinction between parody and satire.[i] Parodies borrow from and comment upon a specific cultural work whereas satires borrow from an array of cultural works to comment on topics outside the original authors or works themselves.[ii] While parodies are generally sheltered under fair use, satires are not. [iii] The Campbell Court further established that parodies necessitate the use of a particular work to make their point.[iv] Conversely, satires can draw on a number of different sources, and thus require greater justification for each act of borrowing.[v]

Although satires arguably have the potential to be transformative and may be deserving of fair use protection, courts after Campbell have been reluctant to regard these works as fair use.[vi] Considering mashups are more akin to satires, in that they often repurpose their chosen source material to reflect on a broader topic, they usually do not qualify for this defense.[vii] In one such seminal case, Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. Penguin Books, the Ninth Circuit refused to extend fair use protection to a literary mashup, titled The Cat NOT in the Hat! (“Cat”), that uses Dr. Seuss’s book, The Cat in the Hat, to lampoon the O.J. Simpson double murder trial.[viii]

Strictly applying the standard from Campbell, the Ninth Circuit reasoned that, while Cat broadly mimics Dr. Seuss’s signature style, the mashup neither holds the original author’s style nor his book up to criticism.[ix] Without doing so, Cat, the court found, was a satirical and not a parodic work.[x] Considering this less protected status, the court presumed that Cat demonstrated “no effort” to create a transformative work with “new expression, meaning or message,” and denied the satirical mashup fair use protection.[xi]

Reinterpreting the Reach of Transformative Value

However, not all courts have adopted such a stringent approach to the fair use doctrine. In Blanch v. Koons, the Second Circuit broadened the scope of fair use protection by determining that the use of a copyrighted work as “raw material,” in furtherance of new creative or communicative objectives, is “transformative.”[i] In effect, Koon’s appropriation of a copyrighted image in a collage painting was protected under fair use because the artist used the image as “fodder” for a commentary on mass media’s social and aesthetic consequences.

Furthermore, the court reasoned that Koons did not intend to “repackage” the copyrighted image, but rather employ it to create “new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings.”[ii] Although Koons’s collage targeted the genre of media advertisements, rather than the individual photograph to further his artistic purposes, this was sufficient justification to merit fair use protection. [iii] Therefore, in a departure from Campbell, the Second Circuit granted fair use protection to creative efforts that reuse an original work to comment on a topic outside the work itself.

This flexible approach was adopted—and the transformative standard was even further loosened—by the Ninth Circuit in the 2013 case Seltzer v. Green Day. Therein, the court posited that a potentially infringing work is “non-transformative” when the work does not alter the expressive content or message of original source material.[iv] In contrast, a potentially infringing work is “transformative” so long as the new expressive content is apparent, even when the new work makes few physical changes to the original material or fails to comment on the original use.[v]

Under this broad conception, the Ninth Circuit concluded that the use of a copyrighted image in one of Green Day’s music videos was transformative.[vi] Treated as “raw material,” the image of a screaming face was repurposed to make a statement about religion that was wholly unrelated to the message of the original picture.[vii] Even though the court found that Green Day did not directly comment on the image itself, the music video was protected under fair use.[viii]

Boldly’s Questionable Transformative Value

Here, the critical inquiry is whether Boldly created a “new expression, meaning, or message” that doesn’t merely replace Dr. Seuss’s original work, Go!. This question, however, cannot be answered confidently in the affirmative when Boldly seems to merely create a sequel to the Seussical tale of exploration with a Star Trek twist. While Boldly draws on Go!’s visual style to convey particular tropes from the Star Trek universe, both texts primarily tell stories of strange circumstances encountered on an adventure.[i]

Nevertheless, the ComicMix court determined that Boldly was “no doubt transformative” because the mashup combines the two disparate worlds of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek into one unique work.[ii] The court further reasoned that Boldly has a different intrinsic meaning and function than Go!.[iii] While Go! is an illustrated book with an “uplifting message” that appeals to graduating high school and college seniors, Boldly has an uplifting message that is tailored to fans of Star Trek’s original series.[iv] However, this analysis seems unsatisfactory. Considering that both texts are similar “uplifting” tales of adventure, Boldly is labeled as a transformative work simply because it is directed towards a niche audience.

Credit: United States Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit, Attachment to the Opinion in Dr. Seuss Enters. v. Penguin Books.

Within the Campbell decision, 2 Live Crew’s rap song undoubtedly appealed to a different audience than Orbison’s musical number. Nevertheless, the essence of what is transformative in 2 Live Crew’s work is that the song intended to leverage the juxtaposition of contrasting cultural styles to make a larger, more critical point. Here, an inquiry into ComicMix’s rationale for re-appropriating two significant pieces of popular culture is markedly absent from the district court’s fair use analysis. Because no critical point is readily discernable from the choice to mash Dr. Seuss and Star Trek together, the creators of Boldly seem to simply draw from two popular canons with the purpose of entertaining an avid Star Trek fanbase. In doing so, the creators’ seemingly want to avoid the “drudgery” involved in thinking up and creating something new. Therefore, under the Campbell Court’s analysis, Boldly, would not qualify as transformative without a discernable new meaning or message.

Additionally, the ComicMix court concluded that Boldly is “highly transformative” from the mere decision to juxtapose Dr. Seuss and Star Trek. In arriving at this conclusion, the ComicMix court seems to grant overbroad fair use protection. Significantly, the Court in Campbell cautioned that almost any revamped version of a classic tune can be interpreted as a commentary on the original, considering how novel old tunes may sound in a new genre.[v] Thus, courts are responsible for diligently applying the fair use analysis to ensure that “not just any commercial takeoff is rationalized post hoc” as a transformative work.[vi]

Here, the conclusion that the mashing of any two disparate works to entertain a certain audience is transformative categorically grants all mashups with transformative status—regardless of the creative intent behind the work. This presumption seemingly extends fair use protection to works that are only nominally transformative and, therefore, weakens the standard of fair use.

Questioning Boldly’s New Insights

Furthermore, the loose fair use stance adopted by the ComicMix court is difficult to reconcile with the precedent established by the Ninth Circuit in Penguin Books. Cat presented a means through which the authors could re-interpret and critique the heavily publicized O.J. trial. Yet, because the satirical mashup did not parody Dr. Seuss’s style or his work, the court concluded that it lacked any transformative value. By denying Cat fair use protection, the Ninth Circuit refused to acknowledge the new insights that could be created by placing Dr. Seuss and O.J. Simpson in dialogue with one another.

Following the court’s logic in Penguin Books, Boldly would also be considered non-transformative because it did not juxtapose the artistic features of its mashup in such a way to parody Dr. Seuss’s work.[i] Further, Boldly is more pronouncedly non-transformative than Cat because, unlike Cat, Boldly barely offers enough new insight on topical subject matter to even qualify as a satire.

However, while Cat was condemned as attention-seeking and exploitative[ii], Boldly was considered “highly transformative” and afforded fair use protection. Although mashups can present a valuable tool for creative play and, as such, are worthy of fair use protection, Boldly does not seem to offer much beyond entertainment value. Instead of social commentary, the commerciality of a Dr. Seuss and Star Trek mashup was at the forefront of the authors’ minds when they went to work on Boldly. According to the ComicMix court, the authors wanted to use the cover of Boldly for posters, mugs and all the merchandise that would reportedly push the book “over the top.”[iii] Perhaps more noticeably than Cat, Boldly seems to capitalize on the popularity of its chosen classic works.

Considering the uphill battle mashups generally encounter attempting to claim fair use, Boldly is a particularly questionable choice to be the mashup that disrupts the court’s general opposition to the art form and receive sweeping fair use protection. Moreover, in rewarding this profit-seeking motive by considering the book transformative, the ComicMix court thus sets somewhat of a poor precedent, protecting nominally transformative work with little critical insight.

Questioning Boldly’s New Purpose

Furthermore, even under the more lenient fair use analysis promulgated by the Second Circuit in Blanch and later adopted by the Ninth Circuit in Seltzer, Boldly does not seem to sufficiently repurpose Go!’s setting and storyline to qualify as transformative.

Go!, the ComicMix court explained, “tells the tale of a young boy setting out on an adventure and discovering and confronting many strange beings and circumstances along his path.” [i] Boldly, too, “tells the tale of the similarly strange beings and circumstances encountered during the voyages of the Star Trek Enterprise.”[ii] While the Seussical landscape in Boldly was recreated to serve as a backdrop to a Trekkian adventure, to the casual reader, it does not seem reimagined to serve a new function.

Nevertheless, the creators of Boldly asserted that they reappropriated the Seussical imagery to offer a group-oriented counterpoint to Go!’s individualist ideal.[iii] Those in support of the mashup, have similarly argued that, in contrast to Go!’s hyper-individualist character, Boldly champions team enterprises that achieve success through the combined efforts of commanders, scientists and engineers. [iv] Additionally, departing from recent Star Trek reboots that are dark and gritty, the creators of Boldly may have borrowed Seussical imagery to highlight the original Star Trek as a story about adventure and make the case for a more hopeful future.[v]

Because the stylistic elements borrowed from Dr. Seuss were intermixed with new writings and illustrations, the court determined that the creators of Boldly “transformed” Go!’s pages into repurposed Star Trek-centric ones. [vi] Following the ComicMix court’s logic, it seems the mere act of combining Dr. Seuss and Star Trek together—to the delight of Star Trek fans—has sufficiently “repurposed” Dr. Seuss’ original works. Again, by this reasoning, any two works mashed together have been purportedly “repurposed” and the mashup creator need not provide any justification for doing so.

Moreover, Boldly’s allegedly transformative purpose was not even fully conceptualized by the mashup creators before they began working on the piece. In fact, at first, the creators did not intend to use Dr. Seuss’s work. According to the district court’s decision, the creators’ original idea was to combine Star Trek themes with the pre-school book Pat the Bunny. They even considered using Fun with Dick & Jane, Goodnight Moon and the Very Hungry Caterpillar before eventually settling on Go! for their mashup.[vii]Although the creators claimed that Boldly now presents a positive message on collaboration, this point was only “generally” argued to the district court.[viii] More like an afterthought, the group-oriented message does not appear to be the catalyst for working with Go! or, much less, creating the mashup.

Although the Second Circuit had previously determined in Blanch that the reappropriation of copyrighted materials may be a transformative use, the court prudently considered Koon’s reason for doing so before extending fair use protection to his work. Here, with only a tenuous justification for copying Dr. Seuss’s copyrighted elements and a cursory fair use analysis by the ComicMix court, Boldly presents a much weaker example of a transformative label.

Similarly, while the Ninth Circuit in Seltzer also established that the reappropriation of copyrighted materials can be transformative, the court primarily granted fair use protection to Green Day’s music video because it served a starkly different artistic function than the copyrighted image. Here, while Boldly focuses on collaboration and Go! emphasizes individualism, the Seussical imagery in both works functions as a means to inspire adventure and exploration.

Instead of using Dr. Seuss as “fodder” or “raw material” in the service of a new story, Dr. Seuss serves as a platform not to repurpose, but rather to repackage Star Trek tropes and themes. Therefore, in light of the Second Circuit’s conception of transformative work in Blanch and the Ninth Circuit’s conception of such work in Seltzer, Boldly should not qualify as transformative.

Credit: United States Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit, Attachment to the Opinion in Dr. Seuss Enters. v. Penguin Books.

Implications of Expanded Copyright Protection for Mashup Artists

Considering the creators of Boldly do intersperse Dr. Seuss illustrations with original text, the mashup alters the expressive content of Seuss’s work to some degree and may not be considered utterly “non-transformative.” Without convincingly delivering a new purpose, message, or insight, the mashup’s transformative value, however, is only marginal. Therefore, the district court arguably mischaracterized the mashup by classifying it as “highly transformative.”

In doing so, the ComicMix court lowered the standard for transformative use to safeguard almost any work with new expressive content. By relaxing the scrutiny needed for fair use analysis, the court allowed a means through which weakly transformative works could receive fair use protection. Simply intermingling two popular stories and sprinkling in some original text would seemingly pass the test—no matter how derivative of the original source material the “new” work might be.

Furthermore, in light of the ComicMix court’s decision in Boldly, the line between “repurposing” and “repackaging” preexisting work becomes blurry. The onus then shifts onto viewers to determine the meaning of the work. While this in itself is not negative, the creator is seemingly absolved from the responsibility of justifying their cultural borrowing, which is a stark departure from the precedent embodied in Campbell. Additionally, without necessitating critical inquiry into the relationship between the source materials used in a mashup, the ComicMix court not only safeguards nominally transformative work, but also removes the incentive for more out-of-the-box thinking.

If the decision stands, copyright laws will not only be destabilized as to disadvantage copyright holders, but also mashup artists themselves. With modern-day advancements in technology, mashups—namely video and music mashups—are easier to create, but also easier to exploit for commercial gain. Subsequently, a new wave of protected mashup creators interested in turning quick profits may produce works that resemble Boldly to capitalize on pre-established fanbases.

Mashups are valuable because they allow creative individuals to process complex ideas; however, this value could very well be overshadowed by the rising tide of lackluster, profit-driven creation. Therefore, mashups with great potential for socio-political dialogue and creative thought could degrade into cheap tricks as the genre’s artistic integrity is compromised by more profit-seeking ventures.

Final Thoughts

Overall, in the context of the transformative standard established in Campbell, Penguin Books, and Blanch, as a creative work, Boldly seems only minimally so. While the book places Dr. Seuss and Star Trek in dialogue with one another, the authors seemingly do not reappropriate or reframe Seussical elements to create a strong new message. Boldly predominately remains an adventure tale that, while tailored to a new audience, imparts readers with the same uplifting message as Go!. Accordingly, Boldly, as a mashup without a cogent social or political message, is an odd choice to be granted with sweeping fair use protection.

If this fair use determination is upheld, the floodgates are seemingly open to those that are more interested in exploiting the popularity of commercial works than exploring new avenues of creative expression. Granting mashups with the presumption of transformative value and seemingly lowering the standard for fair use protection may give mashup artists a long-awaited safety net, but at the cost of potentially cheapening the mashup genre as a whole.

End Notes

[i] See Emerson v. Davies, 8 F. Cas. 615, 619 (C.C.D. Mass. 1845).

[ii] See Andrew S. Long, Mashed Up Videos and Broken Down Copyright: Changing Copyright to Promote the First Amendment Values of Transformative Video, 60 Okla. L. Rev. 317 (2007).

[iii] See Pete Rojas, Bootleg Culture, Salon (August 1, 2002, 11:30 PM), https://www.salon.com/2002/08/01/bootlegs/; Amanda Riter, The Evolution of Mashup Literature: Identifying the Genre Through Jane Austen’s Novels, 6 (Jan. 2017) (MPhil dissertation, De Montfort University), https://dora.dmu.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/2086/14209/Riter%20-%20MPhil%20Edited.pdf.

[iv] Brian Pearl, Girl Talk, Fair Use, And Three Hundred Twenty-Two Reasons For Copyright Reform, 1 N.Y.U. Intell. Prop. & Ent. Law Ledger 19 (2009).

[v] Ritter, supra note 3, at 6.

[vi] Nerd Fest UK, Old Movie Stars Dance to Uptown Funk, YouTube (Oct. 6, 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1F0lBnsnkE.

[vii] Long, supra note 2, at 318-319, 350.

[viii] Id. at 325.

[ix] Id. at 318; Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, 510 U.S. 569, 580-581, 583 (1994).

[x] Dr. Seuss Enters. v. ComicMix, 256 F. Supp. 3d 1099, 1102 (S.D. Cal. 2017).

[xi] Id.

[xii] Id.

[xiii] Dr. Seuss Enters. v. ComicMix, 372 F. Supp. 3d 1101, 1101 (S.D. Cal. 2019).

[xiv] ComicMix, 256 F. Supp. 3d at 1106.

[xv] Id.

[xvi] Id. at 1113.

[xvii] ComicMix, 372 F. Supp. 3d at 1115, 1128.

[xviii] Id. at 1115.

[xix] Editorial Update: The Ninth Circuit decided the case on December 18, 2020. See Dr. Seuss Enters., Ltd. P'ship v. ComicMix Ltd. Liab. Co., 983 F.3d 443 (9th Cir. 2020) (holding that the District Court erred in granting summary judgment to ComicMix on the copyright infringement claim).

[xx] Brief Amici Curiae of Professors Peter S. Menell et al. in Support of Petitioners, Dr. Seuss Enters. v. ComicMix, No. 19-55348 (9th Cir. Aug. 12, 2019).

[xxi] Dr. Seuss Enters. v. ComicMix, 256 F. Supp. 3d 1099, 1104 (S.D. Cal. 2017) (quoting Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, 510 U.S. 569, 576-77 (1994)); 17 U.S.C. § 107.

[xxii] Campbell, 510 U.S. at 577.

[xxiii] 17 U.S.C. § 107.

[xxiv] See Seltzer v. Green Day, 725 F.3d 1170, 1176 (9th Cir. 2013); Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579.

[xxv] Seltzer, 725 F.3d at 1176 (quoting Judge Pierre Leval, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105, 1111 (1990)).

[xxvi] Id.

[xxvii] Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579.

[xxviii] See Seltzer 725 F.3d at 1176.

[xxix] Id. at 579.

[xxx] Campbell, 510 U.S. at 580.

[xxxi] Id. at 583.

[xxxii] Id. at 580-581.

[xxxiii] Id. at 581; Dr. Seuss Enters. v. Penguin Books, 109 F.3d 1394, 1401 (9th Cir. 1997); Tal Dickstein, Fair Use With Dr. Seuss, Law360 (Oct. 20, 2017, 12:46 PM), https://www.law360.com/articles/976329/; Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579.

[xxxiv] Id. at 581; Penguin Books, 109 F.3d at 1401; Tal Dickstein, Fair Use With Dr. Seuss, Law360 (Oct. 20, 2017, 12:46 PM), https://www.law360.com/articles/976329/; Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579.

[xxxv] Campbell, 510 U.S. at 580-581.

[xxxvi] Id. at 581.

[xxxvii] Id at 580-581; Penguin Books, 109 F.3d at 1400-1401.

[xxxviii] Long, supra note 2, at 360.

[xxxix] Dr. Seuss Enters. v. Penguin Books USA, 109 F.3d at 1396.

[xl] Id. at 1401.

[xli] Id.

[xlii] Id.

[xliii] Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 246 (2d Cir. 2006).

[xliv] Id.

[xlv] Id.

[xlvi] Seltzer v. Green Day, 725 F.3d 1170, 1177 (9th Cir. 2013).

[xlvii] Id.

[xlviii] Id. at 1176.

[xlix] Id.

[l] Id. at 1177, 1181.

[li] Dr. Seuss Enters. v. ComicMix, 256 F. Supp 3d 1101, 1106 (S.D. Cal. 2017).

[lii] Id.

[liii] Id. at 1115.

[liv] Id.

[lv] Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, 510 U.S. 569, 599 (1994) (Kennedy, J., concurring).

[lvi] Id. at 600.

[lvii] ComicMix, 256 F. Supp 3d at 1106.

[lviii] Penguin Books, 109 F.3d at 1401.

[lix] Dr. Seuss v. ComicMix, 372 F. Supp 3d 1101, 1108 (S.D. Cal. 2019).

[lx] ComicMix, 256 F. Supp 3d at 1106.

[lxi] Id.

[lxii] Id.

[lxiii] Brief Amici Curiae Professors Mark A. Lemley et al. in Support of Defendants-Appellees and Affirmance, Dr. Seuss Enters. v. ComicMix, No. 19-55348 (9th Cir. Oct 11, 2019).

[lxiv] Id. at 7.

[lxv] ComicMix, 256 F. Supp 3d at 1106.

[lxvi] Dr. Seuss Enters. v. ComicMix, 372 F. Supp 3d 1101, 1107 (S.D. Cal. 2019).

[lxvii] ComicMix, 256 F. Supp 3d at 1106.

About the writer…..

Dana grew up just outside of New York City in Pleasantville, New York. Swapping East Coast winters for Southern California’s sunny skies, Dana moved cross country to study Media Arts and Culture at Occidental College here in LA. Since graduating, she has had the honor of working at Netflix before attending law school to study the legal side of the entertainment industry.